In this post, we explore the foundational idea of waves. First, by considering the motion of a system that is subject to a restoring force, we are led to write down and solve the equation for simple harmonic motion. This sets the stage for considering how patterns of oscillatory motion propagate throughout the spatial extent of a medium according to the wave equation. We solve the wave equation for the case of a vibrating string and draw attention to its discrete spectrum of modes. Our results are then given context by discussing the central role that waves play in blackbody radiation—understanding this was the inception of quantum mechanics—and also in describing motion through spacetime according to the special theory of relativity.

1. Introduction

Wave mechanics are the bedrock of physics. As Professor Howard Georgi writes in The Physics of Waves, “Waves are everywhere; everything waves.” Disturbances that move along a string, over the surface of a pond, through the air making sound, in empty space shining light are all waves. The probability amplitudes of quantum mechanics, encoding where and when a particle is likely to be found, are waves. The general theory of relativity correctly predicted that mass and energy create disturbances in spacetime, radiating outward as gravitational waves.

That wave phenomena are found in so many disparate cases suggests that they share a common formulation. We begin our search for their equations by considering the oscillation of an object about a fixed point.

2. Simple harmonic motion

Consider a point-like object with mass subject to the force

The minus sign makes this a restoring force: as the object moves away from the origin, pulls back with strength determined by

and the object eventually turns around. Inertia carries it through the origin, beyond which

flips direction to keep pulling the object back again. Without intervention, the object will forever continue in this simple harmonic motion. Its stability and simplicity justifies its ubiquity in the world.

The equation of motion of this system, derived from combining Newton’s second law of motion with equation (1), tells us why it moves as it does:

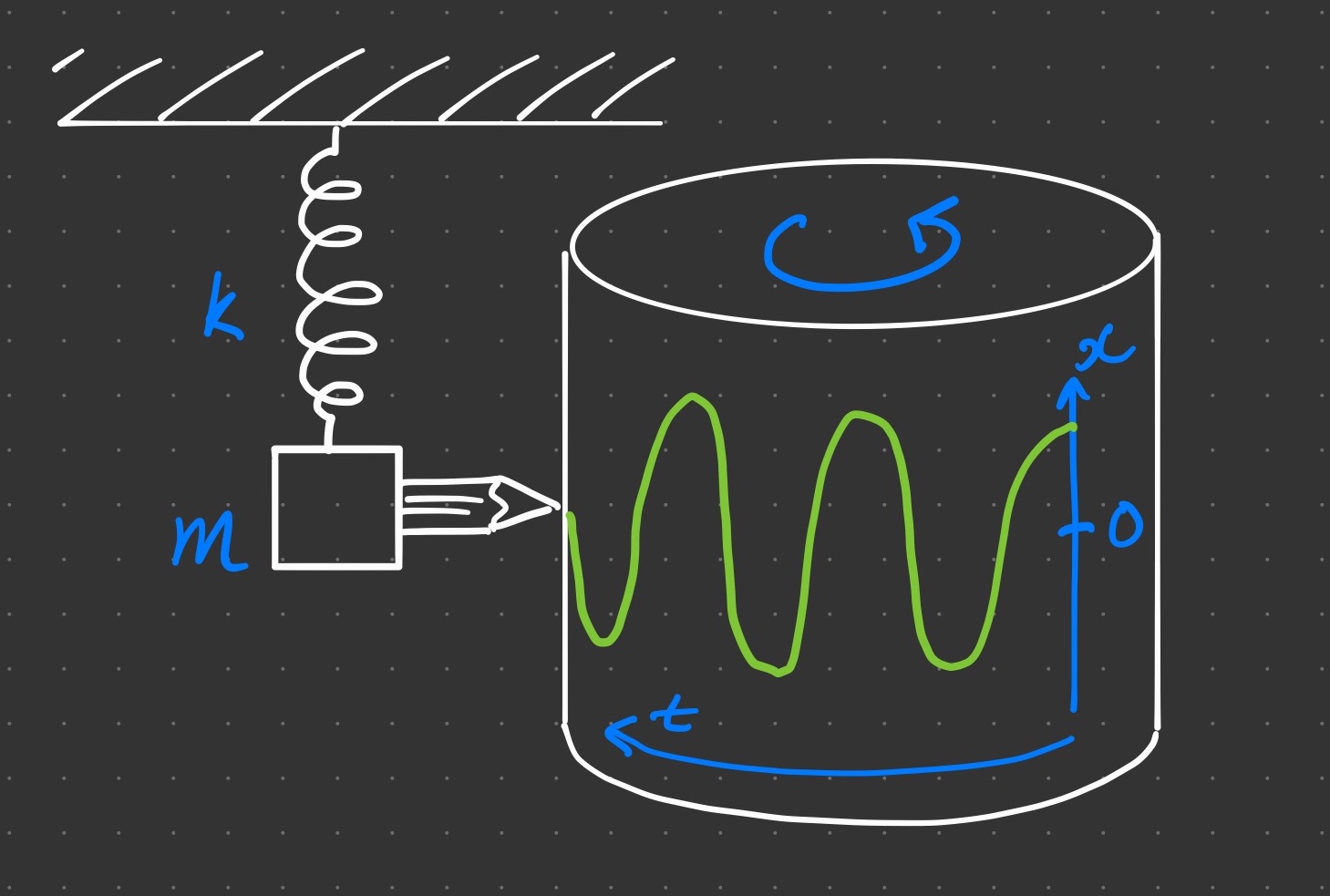

Solving this ordinary differential equation tells us exactly how the system moves. We often solve such equations by guesswork, so let’s see what might look like by sticking a pencil to the object to trace a curve on a drum of paper.

The object traces out a sinusoidal function, which indeed satisfies the equation of motion (2) because its second derivative is proportional to the original function. Check that the following guess for any and

works

We dropped the vector notation for simplicity, and the frequency is related to the parameters

and

in the equation of motion (2) by

Lest for all time, the first set of parentheses must always add up to zero. We learn that

, which behaves intuitively: stronger force or smaller mass increases oscillation frequency.

The equation of motion (2) is a second order differential equation in time, so we need two initial conditions to fix and

to get the particular solution. In the figure above, we have

and

, meaning that the object was lifted a distance

and released from rest at

. Therefore,

,

, and the particular solution is

for

.

Simple harmonic motion is extremely important in physics and comes up often. When the equation of motion (2) applies to a complex-valued function instead of

, the general solution is the phase-shifted complex exponential

This is equivalent to and corresponds to a point in the complex plane orbiting around the origin with distance

and angular frequency

. Note that the real part of

gives back

.

3. The wave equation

Simple harmonic motion describes the to-and-fro vibration of a point-like object. In contrast, a medium with spatial extent like the one-dimensional string, the two-dimensional drum skin, or the three-dimensional air filling a room, vibrates in more complicated patterns called waves. The equations of motion for waves propagating through a medium is the all-important wave equation, our focus for today,

where the operator takes partial derivatives with respect to the spatial dimension of each vector component. The wave equation tells us why all waves moves as they do. Note the following differences from equation (2) for simple harmonic motion. We now have a partial differential equation in three spatial dimensions. The

has been repurposed to point to the patch of the medium, whose displacement is measured by the multivariate function

, telling us exactly how a wave moves. Dimensional analysis assigns units of

to

; it is the wave speed.

Now, consider the motion of a string whose spatial extent lives along the -axis. For this one-dimensional system, replace

in the wave equation (7). This equation is tricker to solve but worth working through. It has two derivatives in time and two in space, so a particular solution will require two initial conditions and two boundary conditions. Suppose the string is fixed at both ends, and we freeze a video of it at time

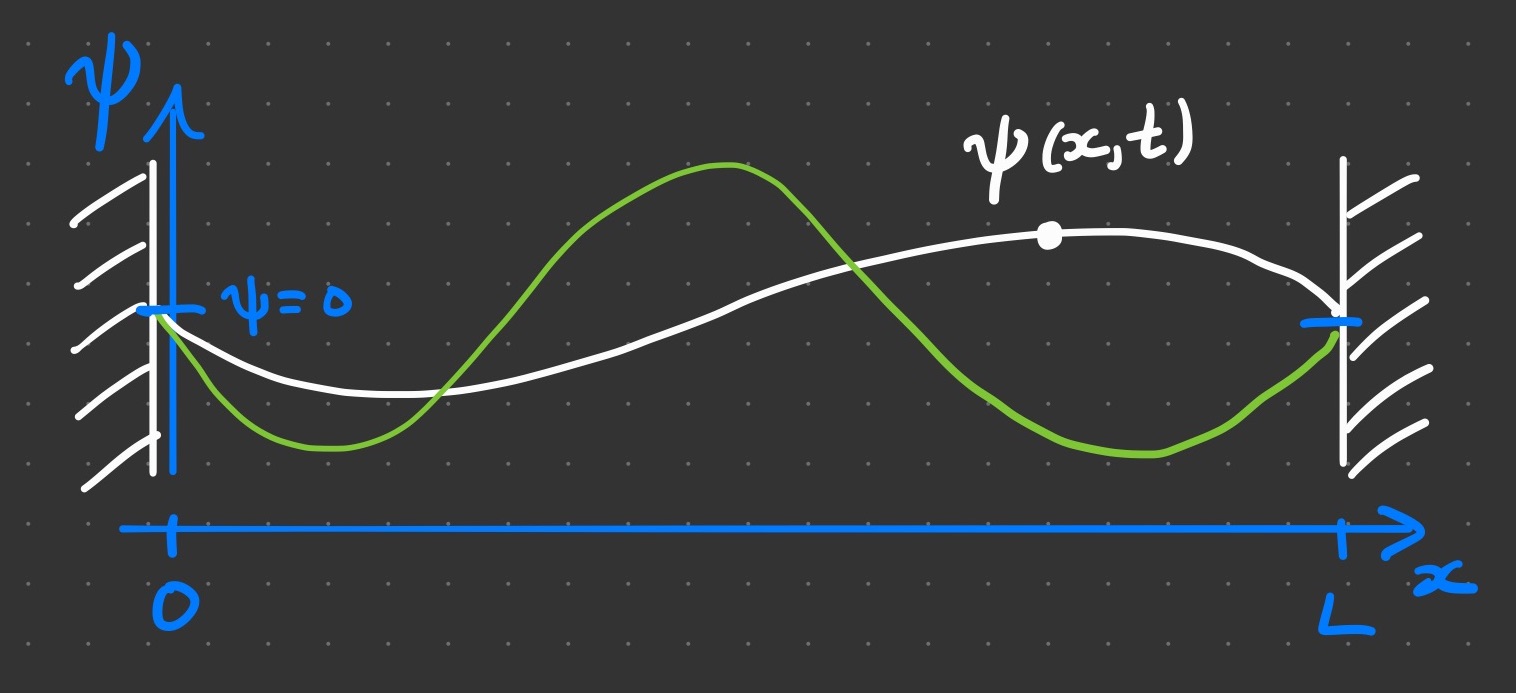

. It might look like one of the example strings drawn below.

These look like sinusoids, perhaps related to simple harmonic motion over space. Now imagine letting the video play; focus on one piece of string at position . I would wiggle up and down, much like the simple harmonic motion of the previous section. These observations suggest that solutions to the wave equation may be separated into two independent functions:

. Plugging into the wave equation (7) and separating variables reads

Since they depend on different variables, each side of this equation must be the same constant value . So, the wave equation breaks into a pair of independent equations, each one indeed resembling the equation for simple harmonic motion (2):

We start by solving equation (9) with the boundary conditions , meaning that the string is fixed at both ends. Writing

as a linear operator

acting on the vector

turns this differential-equations problem into one of linear algebra

, with

being the identity matrix. Three possibilities come up. If

, then

is real, and solutions are real-valued exponential functions

. These won’t work because at least one of the boundary conditions will be violated. If

, then the solution is the polynomial

, which also violates the boundary conditions. This leaves us with

, so

, leading to the complex-valued exponential functions

. Recall from equation (6) that these are secretly sinusoids

that can satisfy the boundary conditions and

. The latter condition is very important: it says that our solution only works for the special values

called discrete integer modes. Only sine functions with wavelengths proportional to half-integer multiples of the string length are allowed, and so we find

Now, let us turn to the other equation of motion (10). This one requires two initial conditions: first, the string starts out after being plucked with some shape ; second, the the initial speed of each piece of the string given by

. We already know that

must be given by equation (13) for certain coefficients

. The form for

is subtler. The ends at

and

will not move if

resembles equation (13). Also,

must contain the speed

, and its antiderivative must be consistent with

so that

. Check that the following works

and leads to the solution

with coefficients and

determined by

and

.

Therefore, the wave equation (7) is solved for our initial and boundary conditions by

This solution for a string fixed at both ends as is actually a whole family of solutions, each one a particular solution corresponding to specific functions and

written as a Fourier series with coefficients

and

. In fact, the general solution of the wave equation is a vast space of functions, containing all the ways that any waveform could propagate. Any smooth wave- or pulse-like function that can be written in the form

will satisfy the wave equation for some initial and boundary conditions.

4. Blackbody radiation

At the turn of the twentieth century, in the year 1900, the wave equation was at the heart of what would spark the birth of quantum mechanics. The spectral radiance of red-hot objects like the Sun, other stars, or heated metal could not be explained. Why do these objects all glow with the same spectrum of light, its peak occurring at a frequency that shifts with the temperature of object? A blackbody is the idealization of such hot objects—think of it as a hot box of light. We already knew by then that light is an electromagnetic wave whose electric field

and magnetic field

each satisfy the wave equation

By the way, the wave speed in this case is , the speed of light. This speed is so important—a fundamental constant of our universe—that we redefined the length of the meter to make this number exact. Its magic is that you will always measure light traveling exactly at

relative to you, no matter how fast you (and your instruments) are moving.

Now, because light is a special arrangement of and

, we only need to worry about the electric field here. It has boundary conditions

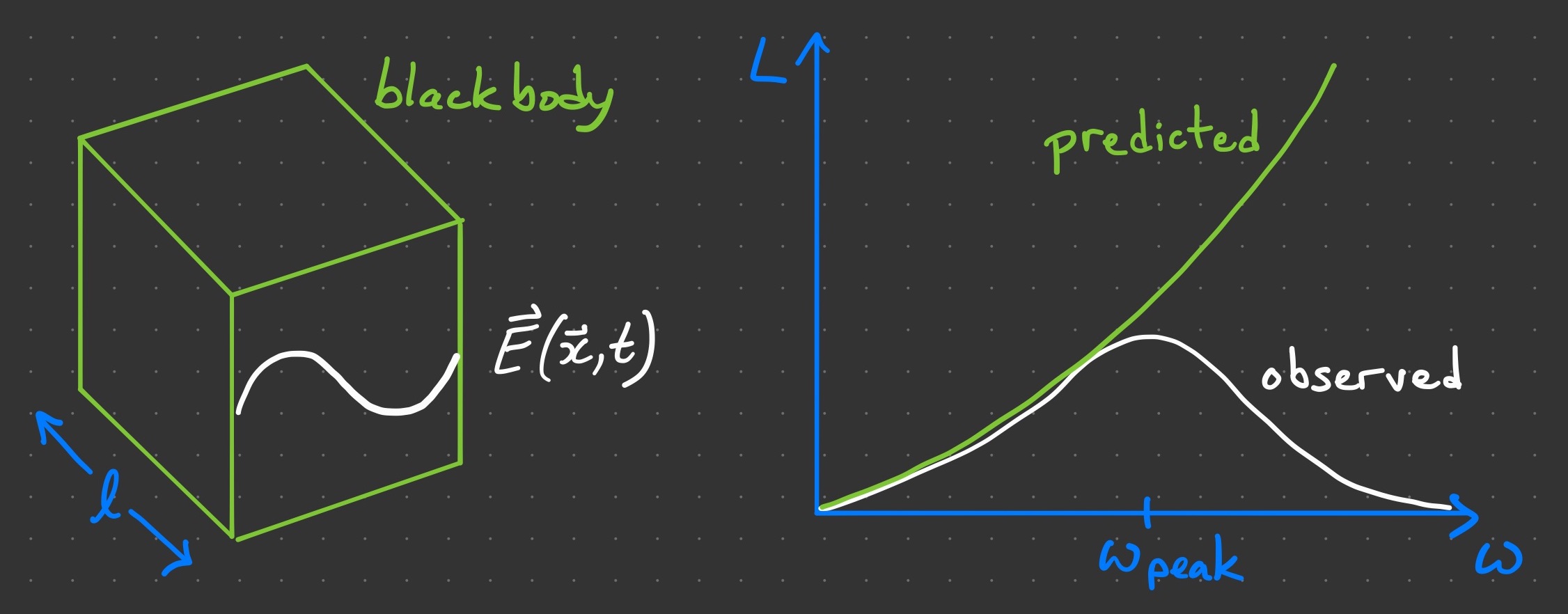

, meaning that it is fixed anywhere on the sides of the box. It is sufficient to consider this boundary value problem along one dimension of the box to see why we could not explain the spectral radiance

emitted by a blackbody.

Just like our string in the previous section, the electric field satisfies the wave equation for sinusoids of shape as in equation (13). Therefore, like the string,

also has discrete integer modes that correspond to the frequencies

Though only one wave of frequency could fit along one dimension, we could fit two waves with higher frequency

in the same space. In three dimensions, the number of waves that we could put into our box grows quickly, namely, with

. Therein lies the problem. The graph above plots our prediction that the spectral radiance

should increase without bound for higher and higher frequencies (gold curve), but it actually doesn’t do that (white curve). Our theory is not even wrong; it predicts an unphysical situation where an infinite amount high-frequency light pours out of the box! This problem was poetically called the ultraviolet catastrophe, and by solving it, we discovered quantum mechanics.

Our prediction assumed that all modes have the same energy cost, a result from statistical physics known as the equipartition theorem. One can spend every bit of their energy budget on making red light, or blue light, or any color of light. The stroke of genius came to Max Planck in the year 1900. What if light was not a continuous fluid but instead was granular—made up of discrete packets, each one called a quantum? By assigning each quantum of light the cost , Planck found that the ultraviolet catastrophe disappeared and that the predicted spectrum matched observation perfectly. Now you could not spend your entire energy budget on making any color of light because each color requires you to divide your budget into differently sized quanta of

. So, you might be able to make one thousand red quanta or, instead, make only one hundred blue quanta with left over energy less than

. And some ultraviolet quanta would be too costly to make at all.

The quantum of light eventually came to be known as the photon and the all-important , another fundamental constant of our universe, as the Planck constant. That

is non-zero implies everything is made up of particles.

5. Motion in spacetime

Albert Einstein proposed the special theory of relativity in 1905, which compelled us to recognize the speed of light as the ultimate speed limit in our universe. The idea that a person on the street, another on a moving train, and a third in a spaceship would all measure the same light pulse to be traveling at exactly

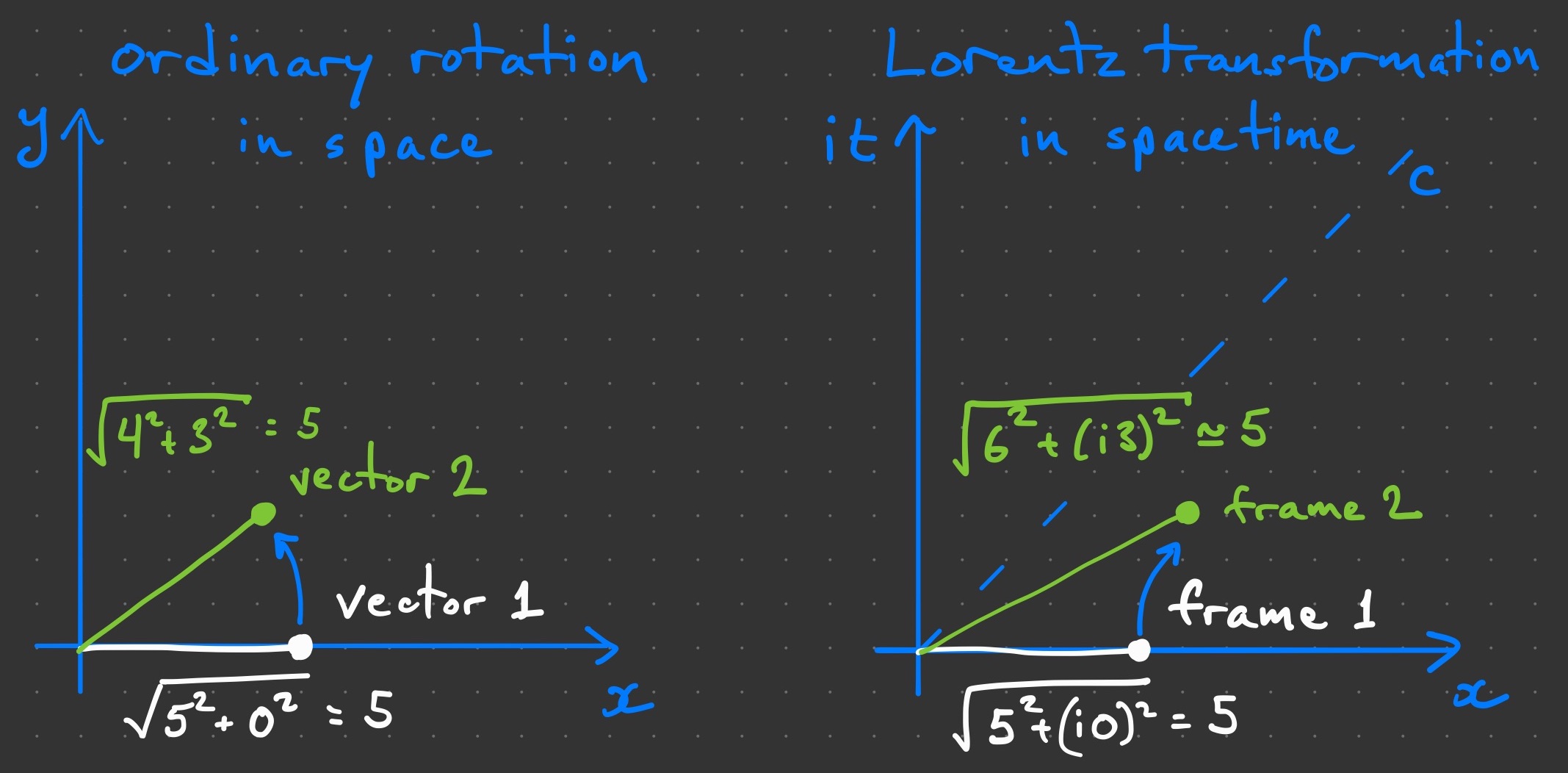

relative to their own speed seems counterintuitive. Nevertheless, this is correct. That they individually see the light pulse receding from them at exactly the same number of meters per second, implies that their yardsticks and stopwatches are measuring different lengths and durations. Indeed, space and time are relative quantities that mix into each other according to rules called Lorentz transformations. Consistency, however, requires that one quantity be absolute: the magnitude of vectors made up of space and time components that live in a vector space aptly named spacetime.

Think of space and time as being the components of a vector as shown above. A Lorentz transformation is similar to ordinary rotation because it mixes vector components while keeping magnitude fixed. The key difference is that the time component is not but

, so that the magnitude of the vector is not

but instead

. The Lorentz transformation shown above corresponds to switching from frame 1, which is at rest with respect to the event measured to be at position

and time

, to frame 2, which is moving to the left and so measures this event to occur at a farther location

and at a later time

. Note the unchanged magnitude.

How then can we describe waves propagating through a field in an observer-independent way? The first step is to redefine the field over spacetime by replacing

and

with the four-vector

that lives in spacetime. Now the field is written as

, and we can switch between frames using Lorentz transformations that mix

and

while keeping the magnitude of

unchanged. The second step is to rewrite the wave equation for

. Moving everything to the left and treating the derivatives like linear operators acting on the “vector”

, we obtain

Because the wave equation is so important in modern physics, we write everything in the parentheses in shorthand as the operator called the d’Alembertian. Since Lorentz transformations preserves the four-vector magnitudes of spacetime, our field and waves propagating through it are described in an observer-independent way by

, the simplest Lorentz-invariant equation of motion. Its solution is obtained in the same way that we solved the wave equation for our vibrating string: by finding

and

and multiplying them together. This yields the plane-wave solutions

, which includes a conventional factor of

in the exponent making the

term positive and the

term negative. This can be written entirely in four-vector notation as

where is the four-momentum. The lowered index

basically means that

is a row vector, so

is an inner product

or

.

Because the environment (and everybody in it) that we interact with moves slowly in comparison to , the space and time that we all experience is virtually absolute. So meeting up in class after spring break or Zooming with distant friends on weekends all works out fairly well. In contrast, if Captain Picard and his crew were ripping around the galaxy close to

(nevermind warp speed), then in reality they would be out of sync with everyone else in the federation. It would be a total mess. But that’s the way the world really works, and the equations for how things look

and move

are exact, no matter how fast we go.

6. Outlook

To summarize, we explored the central role that waves have played throughout the history of physics. A point-like object will undergo simple harmonic motion when subject to the restoring force from a spring, an attractive gravitational, electric, magnetic potential, etc. In contrast, a medium that has spatial extent will propagate waves throughout when it is subjected to a general disturbance like a pebble dropped into a pond, a clap heard in a room, or the light radiating away from a distant star.

How remarkable it is that intrinsic facts about nature were discovered by studying the waves of seemingly unrelated things. This was possible only because we were able to realize that the phenomena were in fact deeply unified. The recognition that the speed of light and Planck’s constant are fundamental for the structure of the universe compelled us to go beyond our classical picture and recast our understanding around relativity and quantum mechanics. Perhaps we may take the view that if the story of waves is characteristic of nature’s hidden unity, then there will be more to follow.