In today’s post, we introduce the six postulates of quantum mechanics. Together, they establish the vector as the fundamental object of the theory—that which provides the quantum description of a physical system. Quantum mechanics uses lots of jargon, so we will translate specialized terms into those commonly used in linear algebra, the mathematical backbone of the theory that lays down the rules that the system follows. With the six postulates defined, we will then see how quantum mechanics compares to classical theory: we will see that the Hamilton–Jacobi equations and Newton’s second law of motion emerge from quantum mechanics.

Our principal source is the material in chapters 2 and 3 from the textbook Quantum Mechanics by Claude Cohen-Tannoudji, Bernard Diu, and Franck Laloë.

1. Introduction

We begin with the six postulates of quantum mechanics, which define the mathematical framework the theory. To set the mood, here they are in English: 1) The momentary state of a physical system can be described as a vector in an abstract vector space. 2) Each observable quantity of the physical system can be described as a matrix that acts on the state vector through matrix multiplication. 3) When making a measurement, we will apply the matrix for the quantity being measured to the state vector of the system; the matrix has an eigenvalue decomposition, and the outcome of the measurement will always be one of its eigenvalues. 4) The particular outcome observed will be determined randomly: the eigenvalues most likely to be observed are those with eigenvectors best resembling the state vector just before measurement. 5) Right after the measurement, the state vector will abruptly change to match the eigenvector that corresponds to the eigenvalue observed. 6) Between measurements, the state vector smoothly evolves according to a differential equation associated with the total energy of the system.

That’s it. These six sentences form the core of the theory. But the more you think about it—the abrupt, random changes of the system after measurement—the less the world described makes sense. Yet, we cannot discard the theory. As strange as it is, quantum mechanics has passed all experimental tests attempted so far, the most stringent ones requiring precision well beyond any other theory conceived.

In the next section, we will make the postulates more precise by providing some of the mathematics of the theory. The level of rigor will remain informal but should enable us to better appreciate the consequences of the theory. By proceeding in this way, we aim to demonstrate how theoretical physicists go about their work: mathematical theory first, consequences second, and occasionally `What does it all mean?’ third. The rationale for this approach is simple: for all we can see, the rules of nature are written in mathematics, and nature always sticks to her rules. Therefore, good physical theories cannot afford arbitrary qualities; they must be fully constrained by mathematics. The final arbiter about a theory, of course, is experiment. Physical theories ought to make falsifiable predictions, so that they can be rejected if experiment disagrees with their predictions.

2. The Six Postulates

To define the postulates concisely, we consider our system to be a single particle that lives in one space dimension and one time dimension

However, quantum mechanics applies to any system within our universe.

2.1. First: Quantum States

The first postulate tells us that the momentary state of a physical system can be described as a vector in an abstract vector space.

The quantum state of a particle is fully characterized at a given time by a square-integrable wavefunction We associate a ket

of the state space

with each

such that

Thus, at fixed time , the state is defined by

The wavefunction is the core idea of quantum mechanics and represents a sharp departure from classical physics. In classical mechanics, we only needed a few real numbers to represent the state of a particle at a given time: its position and velocity coordinates. In quantum mechanics, we need one complex number for every point in space to represent the same particle; that is, we need a whole function

We made this enormous change because it turns out that particles do not move the way we first thought they did. More information than what is encoded in classical mechanics is needed to fully describe the state of a particle and what it could do next.

Before getting into this, we need to associate the wavefunction with a vector, which we denote by putting funny brackets around the function

This vector has an infinite number of elements, one for each point

in space, and lives in the infinite-dimensional Hilbert space denoted

The funny brackets come from the bra–ket notation, a brilliant invention by Paul Dirac allowing us to easily distinguish column-vectors called kets written as

from row-vectors called bras written as

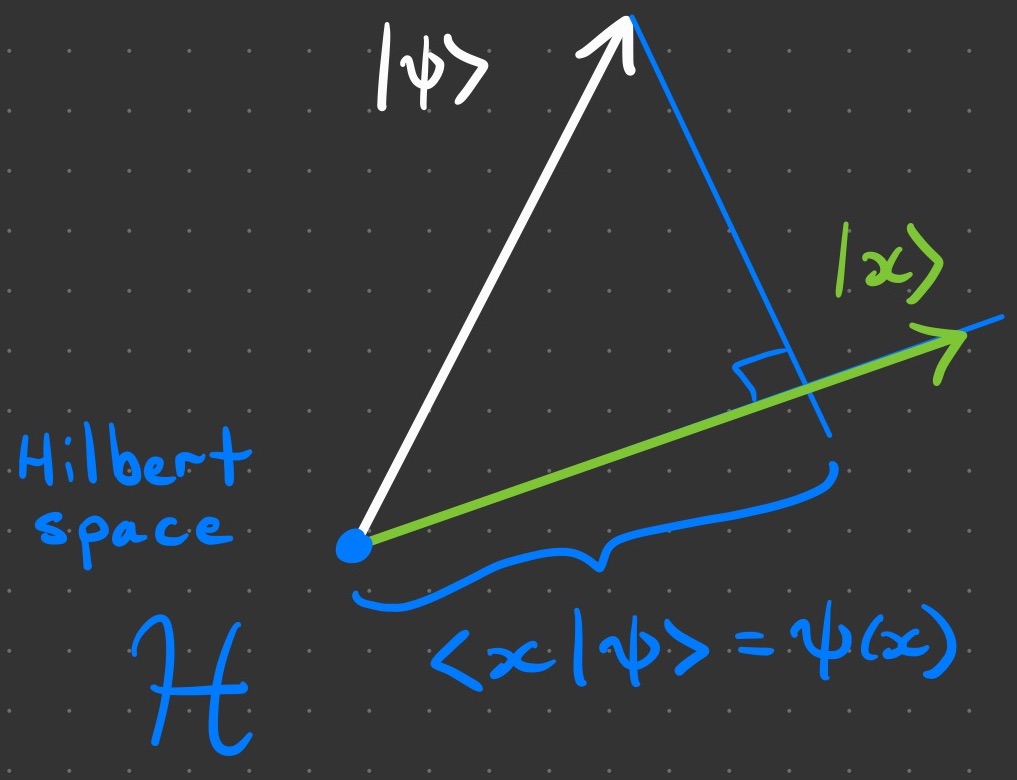

The bra–ket notation will help us leverage the power of linear algebra operations like the inner and outer products, matrix multiplication, and matrix transposition. For example, the inner product was used in equation (1) to explicitly relate wavefunctions to vectors. We can compute the value of the wave function at some point

by taking the inner product between

and the position vector

that essentially has value

in the element corresponding to the point

and has

everywhere else. To take an inner product, we need to transpose one of the vectors before multiplying, and this is what a bra is:

, where the dagger represents a fancy transpose called the adjoint. So,

is indeed the inner product that picks out the the element of

at the point

and multiplies it by

; all other elements are multiplied by

The kets

and

in

are sketched below along with an illustration of the computation

2.2. Second: Observables

The second postulate tells us that each observable quantity of the physical system can be described as a matrix that acts on the state vector through matrix multiplication.

Every measurable physical quantity is described by an operator

acting in

We call

an observable. Thus, states are associated with vectors and physical quantities with matrix operators in a vector space.

A measurable quantity can be any number obtained by experiment. We have already seen one such quantity, the position of the particle; call it The corresponding observable for

is the matrix

that lives in

So, to measure the position of the particle with wavefunction

, we would consider the matrix product:

Although a matrix multiplying a vector yields another vector, also in , we will soon see that the purpose of the observable is not to transform the vector

but rather to analyze it. For now, we can say that all observables are square matrices whose set of orthogonal eigenvectors span

or a proper subset of

Therefore, we can think of the matrix product

as the observable

representing the vector

or its projection in the subspace spanned by the eigenvectors of

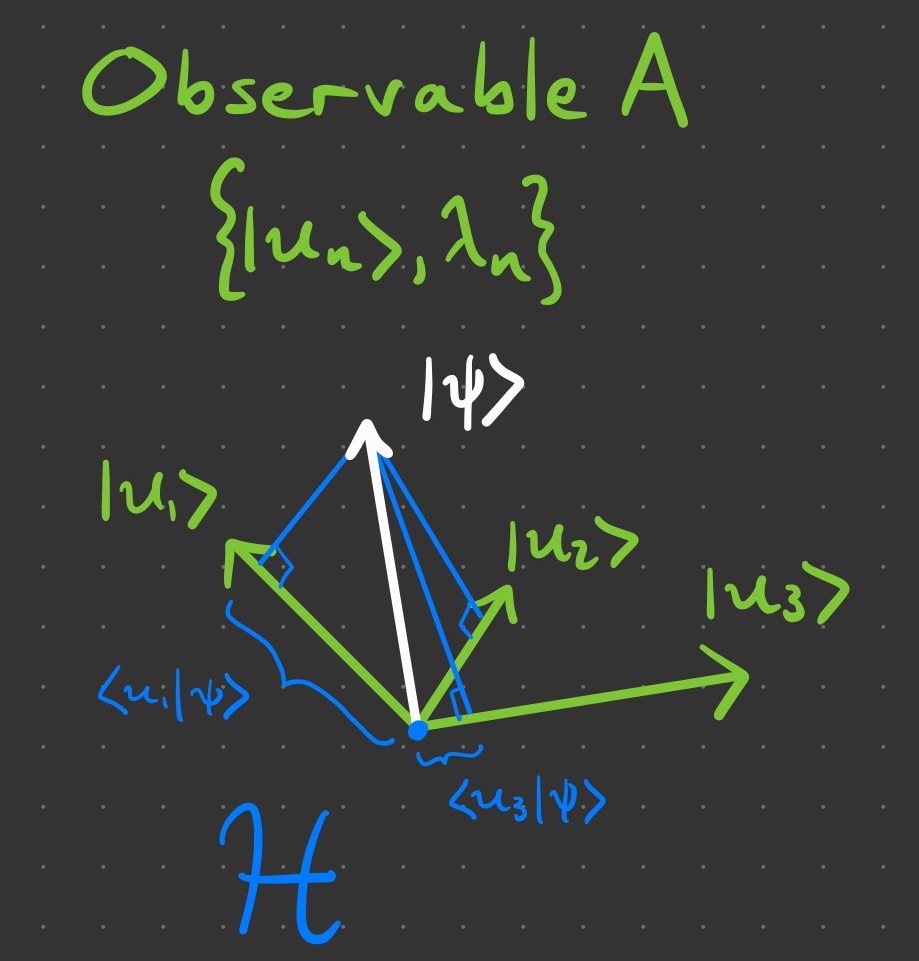

This idea will feature prominently in the remaining postulates, so we illustrate this for a generic physical quantity

below.

Returning to our familiar example of position , the eigenvectors corresponding of the observable

are simply the position vectors

for each point

in space. They are indeed orthogonal from each other. In this case, the set

spans all of

, but this need not be the case for a general quantity

As you may have guessed, the quantity

is of special importance: it defines space itself! Another important quantity is the momentum of the particle

, and we could have written the wavefunction using the set of all possible momentum vectors, such that

The main point is that any physical quantity is associated with a matrix

called an observable that provides a basis of eigenvectors for analyzing a state vector

2.3. Third: Measurement

The third postulate tells that when making a measurement, we must apply the matrix for the quantity being measured to the state vector of the system. The matrix has an eigenvalue decomposition, and the outcome of the measurement will always be one of its eigenvalues.

The only possible outcomes of a measurement of are one of the eigenvalues of

Thus, if

is an eigenvector of

with real eigenvalue

, then measuring

entails

and the observed outcome is the real number

Since the Hilbert space is infinite dimensional, any physical quantity whose eigenvectors span

must have an infinite number of eigenvectors. For example,

has an infinitude of eigenvectors

At the other extreme, some physical quantities have very few possible outcomes. For example, the famous Stern–Gerlach experiment measured whether the spin angular momentum of a silver atom was either

or

Therefore, the spin quantity

has an observable

with only two eigenvectors: spin-up

with

or spin-down

with

In this case, it is implied that the state of the silver atom

also has labels for position and other quantities, but these can be omitted when measuring

if the outcome would either fully determine or have no effect on the other quantities.

The definition above labels the set of eigenvectors of as

Were the state of the system

for some

, then the measurement of the quantity

would be guaranteed to return the value

If we repeated the exact same experiment many times, we would always measure the same value

However, were the system a superposition of eigenstates, say

, then it is unclear what the measurement would be. It could either be

or

but neither both (surely!) nor anything in between. We will see in the next postulate that the outcome will be purely random.

2.4. Fourth: Random Outcomes

The fourth postulate tells us that the particular outcome observed is determined randomly: the eigenvalues most likely to be observed are those with eigenvectors that best resemble the state vector immediately before measurement.

For simplicity, we assume that has a discrete and non-degenerate eigenvalue spectrum. When a measurement of

is made on a system in state

, the probability of observing the outcome

is given by

where vectors are normalized to unit length

That we cannot predict the outcome of a single measurement with certainty—even with perfect information about the system—is a radical departure from classical, deterministic physics. However, the randomness of individual outcomes does not imply that there is no order in the universe and that nothing is predictable. This postulate tells us that we can predict quantitatively how the measurements from a large number of repeated experiments will be distributed across the range, or spectrum, of possible outcomes.

The above paragraph interprets the left-hand side of equation (3), namely, the probabilities Let us now think about how the right-hand side of the equation calculates these probabilities. First, we see an inner product between the

eigenvector

and the state vector

In words, the inner product

tells us what these two vectors have in common, or somewhat more precisely, the amplitude of the projection of one vector onto the other. Because the Hilbert space

represents complex-valued wavefunctions

and is a complex vector space, its inner product is in general also complex-valued. This is why we see the absolute value bars around the inner product in equation (3), so to yield a non-negative real number. Probabilities only make sense for numbers in the unit interval

, which explains why all state vectors and eigenvectors must always have unit length. Finally, there is a square in the expression

Without the square, we still would have probabilities in the unit interval—but they would disagree with experiment. What we do know is the probability of observing a particular outcome goes as the square of the amplitude. That the exponent is exactly

suggests a geometrical justification, like an inverse-square law, where probability is conserved in toto but spreads out over some surface area.

There is also an important case when the state of the system is exactly equal to one of the matrix eigenvectors Then, the prediction is that the probability of observing

is

, and the probability of observing any other eigenvalue is

This turns out to be a crucial point for quantum mechanics, as we will see in the next postulate, which leads to the following sensible behavior. Were we to make a rapid succession of measurements, the first outcome observed would be random for general

, but subsequent outcomes would be identical to the first. Thus, measurement affects the system by immediately putting it in a state consistent with the outcome. This process involving measurement, probability, and collapse is illustrated below.

2.5. Fifth: Wavefunction Collapse

The fifth postulate tells us that right after the measurement, the state vector abruptly changes by becoming equal to the matrix eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue that was observed.

If the measurement of on the system in state

yields the result

, then the state immediately after the measurement becomes the normalized projection of

onto the eigensubspace associate with

In the non-degenerate case, the eigensubspace is , thus,

Here we see explicitly how measurement changes the wavefunction While in general, the system state may be in some superposition of possible measurement outcomes, the act of measurement immediately puts the system into a state compatible with the observed outcome

and incompatible with all other alternative outcomes

for

, as prescribed in the mapping (4). This measurement-induced state change is known as wavefunction collapse because it destroys any superposition of outcome states the system may have occupied before measurement.

The mapping shown in (4) uses the projection operator corresponding to the observed eigenvalue

In the simplest case, there is only one eigenvector

where

This is called the non-degenerate case, and the mapping must simply be

Notice how this would happen if the operator is

Here, we really appreciate the power of the bra–ket notation. A ket (column vector) multiplying a bra (row vector) gives a matrix (an outer product), which is indeed an operator! The numerator of the mapping (4) becomes

This is nothing more than the ket

scaled by the inner product

, i.e., a number. Notice also that the inner product cannot be zero for this mapping because the fourth postulate states that the probability in equation (3) of observing

would also be zero. Finally, plugging the outer product in for

in the denominator of (4) yields

, where the star denotes the complex conjugate and reverses the order of the bra and ket. Well, this cancels the inner product in the numerator, giving us exactly what we came for,

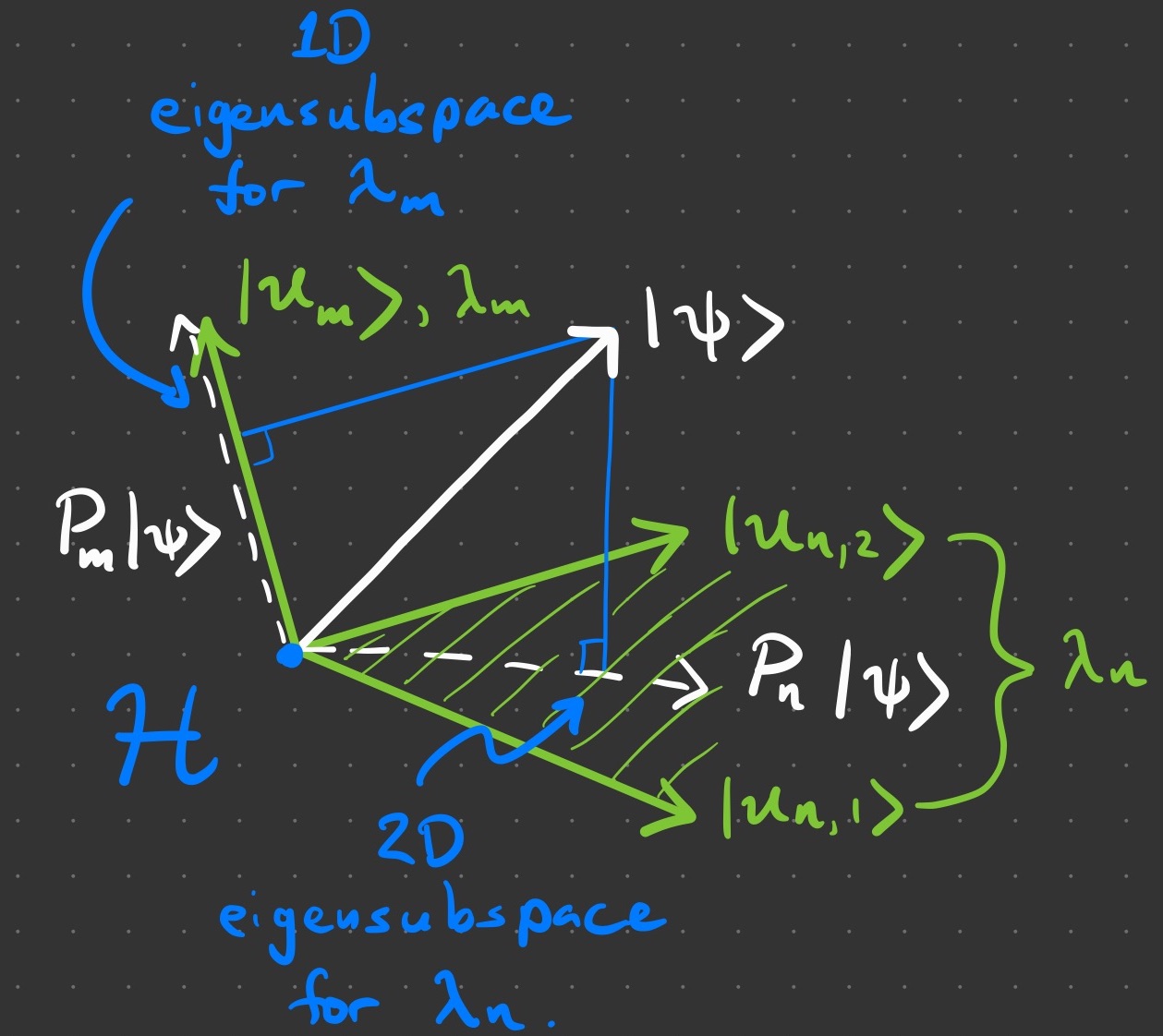

We bothered ourselves with the projection operator because, in general, an eigenvalue will correspond to subspace spanned by two or more eigenvectors, such that

holds for

In this case, the operator

must do something fancier than

It must project

onto the eigensubspace spanned by

by keeping the components of

that are compatible with

and setting the rest to zero. This is achieved if we generalize our projection operator to be the sum

Notice how this collapses back to the simple case for

The action of a projector onto a

subspace is illustrated below. You can check that the mapping (4) has unit length in this case, too.

2.6. Sixth: Wavefunction Evolution

The sixth postulate tells us that between measurements, the state vector smoothly evolves according to a differential equation associated with the system’s total energy.

The evolution of the state is governed by the Schrödinger equation

where is the Hamiltonian operator, the observable associated with the total energy of the system. An important example is the spinless particle of mass

in a scalar potential

, which has the Hamiltonian

The sixth and final postulate establishes the dynamics of quantum mechanics. The Schrödinger equation (5) is a linear first-order differential equation in time that prescribes the state vector at some moment, say

, to be the value of the function

at

The function

must satisfy the differential equation (5), whose solutions are determined by the Hamiltonian operator

, also a function of time in general. A lot of physics is encoded into equations (5) and (6). Perhaps most important is the appearance of the Planck constant

, whence the term quantum (see the post Everything Waves). Here, we touch on the relevant points to our discussion.

First, is indeed an observable acting on

Like all observables,

has an eigenvalue decomposition. Its eigenvalues quantify the all-important total energy of the system, thus their special symbol

instead of our generic

When the total energy is constant, then the system is said to be conservative, and we simply write the Hamiltonian as

with eigenvalue spectrum

The energy of a conservative system transforms without loss from kinetic to potential and back again, such as in the case of a particle trapped in a potential well

with kinetic energy

This is what is prescribed by equation (6).

Second, as mentioned before, the position and momentum

are actually observables. It is sensible to rewrite equation (6) in terms of the matrix operators

and

; notice how

immediately makes sense as a matrix acting on the state vector

It will also be of central importance to make the connection between the variables

and the observables

when we explore the quantum origin of classical mechanics in the next section.

Finally, it is worth considering solutions to the Schrödinger equation for constant Hamiltonian Suppose at time

we had

Then a measurement of the total energy would yield

, and

would consequently not change. The general solution to the Schrödinger equation (being of first-order) has an exponential form

, varying only by a global phase factor. Although the global phase rotates over time, it has no effect on any observable because the square of the amplitude will always replace it by

Therefore, states

at different times are always physically indistinguishable. Had we started with the more general case, a superposition of eigenstates

, then our solution to the Schrödinger equation (being linear) would involve relative phase factors

Relative phases will interfere before the amplitude is squared, so states

at different times are in fact physically distinguishable.

So much for the postulates of quantum mechanics. It would be natural to feel uneasy with the caricatural presentation given here. Indeed, this is no substitute for a rigorous course of study. Having seen the core of the theory will hopefully help you decide whether to follow the rabbit hole any deeper.

3. Classical Mechanics Redux

In this final section, we derive the laws of classical mechanics using what we have learned above. We will also need new material, but don’t sweat it if you have not seen it before; consider it an opportunity to dig deeper. Our goal here is merely to illustrate how the classical emerges from the quantum without diving into detail.

We begin with our observables for position and momentum

and compute their expectation, or mean values,

Notice how the bra–ket notation makes it clear that each expectation is simply a scalar function of time, very much how we describe a classical particle using and

These expectations are the average position and momentum obtained by repeating many experiments measuring

and

of our system in state

We would like to know the dynamics for these operators of average position and momentum. The dynamics are the rules that determine how our system goes from one state to the next; they are known as the equations of motion.

Given a system with Hamiltonian , the equations of motion for any constant operator

were found by Werner Heisenberg to be

where is called the commutator of

and

Let us take a moment to discuss commutation relations between operators because they are extremely important in quantum mechanics. Operators are represented as matrices, so the order of matrix multiplication matters, unlike scalars which always commute (e.g., ). A non-vanishing commutation relation implies that the eigenstates of the two operators are not compatible, so the system cannot simultaneously be in an eigenstate for both operators. Therefore, a non-vanishing commutation relation between two operators means that you cannot measure both quantities simultaneously. The most famous example comes from the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which states that one cannot measure position and momentum simultaneously. This is encoded in the all-important canonical commutation relations

where index the spatial directions

, and

for

and

otherwise is called the Kronecker

-function.

Now, let us return to the task at hand. Our system has Hamiltonian operator

and we can plug our and

operators in place of

Notice that any operator

commutes with itself, i.e.,

This implies that

as well as

Altogether, we find our equations of motion become

Using the canonical commutation relations in equation (10), the commutator in the equations of motion for position (12) is

The commutator in the equations of motion for momentum (13) is found using the correspondence between the momentum and differential operators , yielding

Restoring these results into the equations of motion (12) and (13) reads

which is known as Ehrenfest’s theorem in quantum mechanics.

By interpreting the averages of the position and momentum operators as the scalar variables of classical mechanics, and

, we find the Hamilton–Jacobi equations of classical mechanics, as advertised. Combining these two equations, we obtain Newton’s second law of motion, where force is defined as the rate-of-change of momentum or, equivalently, as the negative of the gradient of the potential